In the last decades of the 20th century, many large psychiatric hospitals were dismantled, in Sweden and other parts of the world. There were several reasons for this. One was that patients, former patients and staff testified about abuse and neglect. Relatives, journalists, academics and politicians also argued in favour of closure of these hospitals. The buildings also needed renovation. It was often cheaper to shut them down. In addition, at this time, socially oriented psychiatry and patient organisations were strong. Meaningful employment, context and participation in society, non-medical perspectives and treatment models were emphasised as important for recovery.

When they were closed, the buildings stood empty. Those buildings considered architecturally insignificant or located in unattractive districts or regions deteriorated or were demolished. Those considered to be architecturally valuable and located in popular areas, often in cities with a lack of housing, were sold and became residential areas, business parks, hotels and more. In the transformation, the traces of their past, including those of the people who were their patients, were often erased.

At Hisingen, there were two renowned mental hospitals, Lillhagen and St. Jörgen Hospital, both now closed and with many of their buildings demolished. We took a day out on a search for traces of St Jörgen Hospital, formerly known as Gothenburg Hospital. We brought along the book “Göteborgs hospital S:t Jörgen psykiatriskt sjukhus i Västsverige: en minnesbok” [Gothenburg Hospital St Jörgen Psychiatric Hospital in West Sweden: A memorial book] by Ann-Marie Brockman, some maps, and an umbrella. We wanted to find traces, buildings and the hospital’s cemetery.

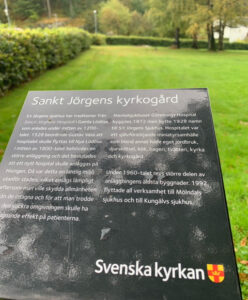

We found the cemetery, a lawn and trees surrounded by a hedge in the middle of the residential area that was built on the site, where some old staff residences are also located. The cemetery was consecrated in 1889 and was used until the 1940s. In addition to 223 patients, the hospital’s first hospital director, as well as other staff and their relatives, were buried there. The graves of the staff and some prominent patients bore names, but the rest of the graves were merely labelled with a stick on which was written the patient’s admission number. In the 1960s, a decision was made to level the cemetery, which probably contributed to our first impression of this as a park, a random place, and not a cemetery.

The Church of Sweden has erected a sign that states that people from Gothenburg Hospital are buried here. It is beautiful and is reminiscent of the memorial that the Västra Götaland region has erected in memory of patients buried at Restad Hospital, Vänersborg. At the same time, something grates. Where are the patients’ voices? Where are the patients’ names? Gunnel Bergstrand, who was herself a patient at Restad in the 50s, is fighting for the abuse committed by psychiatry to be recognised and for focus to always be directed on patients’ experiences and their voices. In the film “The patient is otherwise healthy and alert” Link to the film (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iotxZeHt3v0&t=31s), Gunnel lays a wreath on an anonymous grave and argues that people should be given their names. She feels that memorial plaques can be a way of sweeping the abuse under the rug. More is needed!

Gunnel is not alone in her opinion. During the pandemic in the autumn of 2020, Joel Nordkvist, a politician in Östersund, began to take an interest in stories he heard about how patients from Frösö Mental Hospital who died from the Spanish flu were buried anonymously at Frösö western cemetery. We interviewed him about this. Joel received help from people in the church and the cemetery management, from a journalist for the daily Östersundspost, and from people who provided information about their older relatives. We found out that 59 patients died in the Spanish flu pandemic and an unknown number had been buried at Frösö West Cemetery. Joel is now working for a memorial to these people and for their names to be listed. He says these people had a name, we know when they were born and when they died, because these details are in hospital documents. They should have a worthy funeral and a memorial, just like everyone else. Joel also thinks that this is a form of redress and that we need to acknowledge historical abuse and learn from it. For Joel, it’s also about taking care of the stories of people. Thanks to cemetery personnel having told us about this, for generations, we can re-establish patient graves to a certain extent. We can also recognise the knowledge and insights of the staff in local history. The Parish Committee has decided that a memorial with names will be erected.

As we walk around the old hospital area, we’re thinking about all the traces that have been lost. The term ‘strategic forgetting’ is used to illustrate how those parts of history that are considered ‘difficult’ are deliberately swept away when areas or buildings are re-used. Often, decision-makers and planners assume that people are negatively affected by old mental hospitals. For that reason, they should be made to disappear from the collective consciousness or be remembered in small and formal portions.

We are not so sure that history needs to be ‘forgotten or corrected’. Joel’s work investigating and remembering the patients at Frösö Hospital and the enormous interest his discoveries aroused, with exposure in both local and national media, show that there is an interest in understanding and remembering. In Gothenburg, a street in the Lillhagen district will be named “Kulvertkonstens väg” in reference to the murals created by patients to decorate the walls of the culverts under the hospital. And many people have a relative who was admitted to an institution, perhaps a mental hospital, a home for those with special needs, a reformatory or a children’s home. They probably want to remember. And those who, like Gunnel, live with the effects of the doubtful care they were subjected to have the right to recognition and redress.

We believe that society as a whole, and individuals, are in fact able to remember, recognise historical mistakes and learn from them St. Jörgen Hospital, Gothenburg Hospital, does not need to fade into obscurity. We can learn from the buildings and the site, and from the fate of patients and their stories. And acknowledge that they had names.

Nika Söderlund, Paula Femenias & Elisabeth Punzi